Through theft, intrigue, and base determination, China has risen rapidly from an impoverished, third world nation into one of the great powerhouses of the twenty-first century. In many global industries such as natural resource harvesting, manufacturing, and development, China has solidly filled the vacuum left behind by the United States as it gradually—through some faults of its own—lost its competitive edge.

Tales of China’s success in some of these industries, such as manufacturing, are well known; their consequences (see the Made in China tag on any number of your household items) plain to see. But its dominance in one important industry, one which holds everything from the promise of a lucrative low-carbon future to augmented national security, is not often reported. This industry is commercial nuclear energy. It was born in the United States, and in the United States it came of age.

It is an industry in which the United States led the world for half a century. But one in which American supremacy has been lost through, like so many others, incessantly burdensome regulatory and cost prohibitions.

The Vogtle Nuclear Plant in Georgia, where the most recent units in the United States came online in 2024. Source: Georgia Power

Today we will trace the history of nuclear energy, how the United States ceded its superior position to the Chinese, and what the consequences of this are. For the time being, America remains the foremost producer of nuclear energy in the world, but our edge is quickly eroding. We will then examine what America must do to regain its place at the top.

History of Nuclear Energy in the United States

The dawn of the nuclear age was preceded by several years of experiments which, in rapid succession, unveiled the hidden power locked within the tiny atom. The names of the individuals involved were renowned around the world—Albert Einstein, Otto Hahn, and Niels Bohr to name a few—and these experiments would raise their fame all the more. By their work it became evident that fission, the process through which atoms are split, could be induced into a self-sustaining chain reaction.

But it was the Italian-born American physicist Enrico Fermi who successfully actualized this theory through the construction of the world’s first nuclear reactor underneath the University of Chicago’s squash court in December 1942. Therefore, it was the nuclear reactor, and not its more famous and destructive 1945 counterpart, that truly launched the nuclear age in the United States.

Enrico Fermi, U.S. National Archives

After the war, the United States developed the Atomic Energy Commission to encourage the civilian development of nuclear power. The first electricity-generating reactor, housed in Idaho, was completed shortly after in 1951. By the beginning of the 1970s, over twenty nuclear reactors were operational in the United States, and by its close, the number had risen to more than seventy. Throughout the 20th century, dozens of units would be constructed per decade in the US.

In 1991, the peak of nuclear electricity generation in the United States, there were 112 reactors operational accounting for 22% of national energy generation. Today, the US operates 94 reactors that meet 18.6% of its energy needs. Though a decline from years past, the US accounts for a third of nuclear energy generation globally as the largest producer in the world.

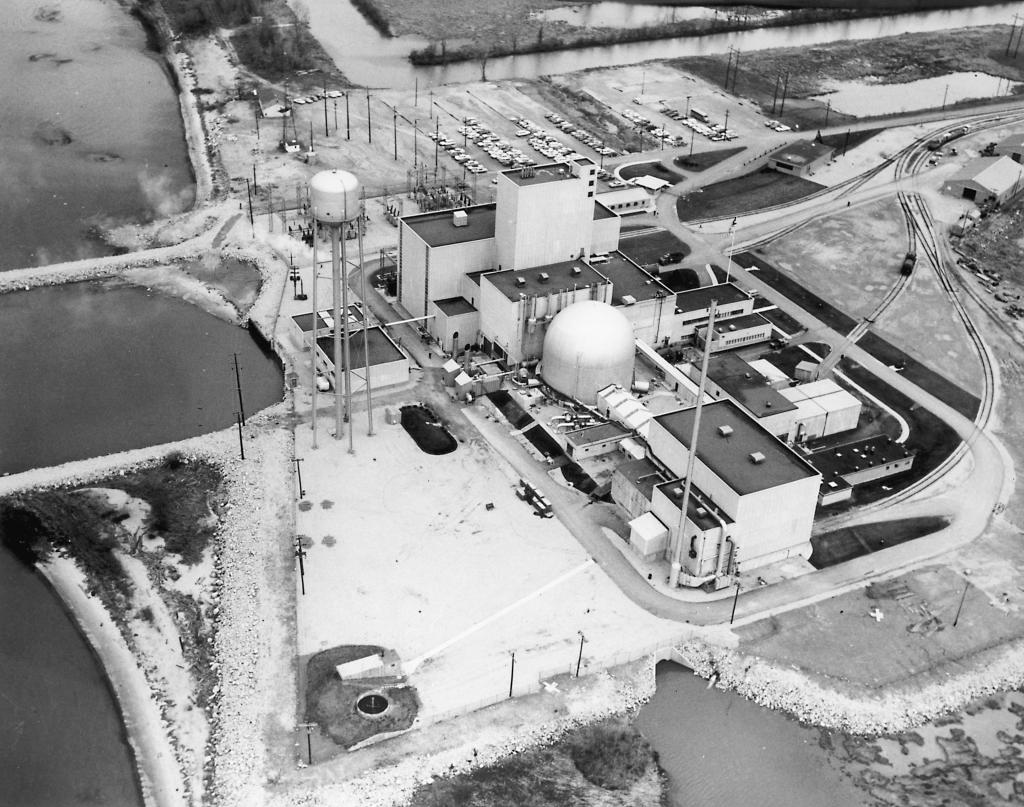

The Shippingport Atomic Power Station, PA. Source: Department of Energy

In the eight decades that nuclear power has existed on the earth, there have been four stages of reactor development, colloquially known as Generations I-IV, and the United States played the foremost role in the design and construction of each.

- Generation I – Early prototype reactors which served as a proof of concept of nuclear power throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The first of these were built in the US, such as the first experimental reactor in Idaho (1951) or the first commercial one in Shippingport, PA (1957).

Shown: Fermi I Nuclear Reactor, MI

- Generation II – Commercial reactors designed to be safe and economical. The bulk of reactors built in the 20th century. Many are operational today. Includes pressurized water reactors (PWRs), boiling water reactors (BWRs), and light water reactors (LWRs). Though economic, Gen II reactors generate high levels of spent fuel. Most built by American companies Westinghouse and General Electric.

Shown: Watts Bar Nuclear Plant, TN

- Generation III – Reactors fitted with significant fuel efficiency, thermal efficiency, and safety improvements. Often retrofitted into existing Gen II designs, these improvements vastly extend the life of reactors. The bulk of these design improvements were once again led by American companies Westinghouse and General Electric.

Shown: Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Plant, Japan. The world’s largest.

- Generation III+ – Further improvements to Gen III reactors to improve their safety and fuel efficiency. Often include passive systems that will work automatically in case of power failure. These reactors have high fuel consumption and therefore generate very little waste.

Shown, Vogtle Units 3 and 4, GA

- Generation IV – Largely theoretical, there are six Gen IV technologies proposed to heighten nuclear energy safety and efficiency, and diversify its fuel sources. Though the US largely assisted in the development of these technologies, China is the only nation which has broken ground on the construction of prototypes.

Shown, Shidaowan-1 Reactor, China

The Rise of Chinese Nuclear Energy Capability

Though the United States for the time being remains the largest producer of nuclear energy in the world, it is widely regarded to have lost its crown.

According to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), “Civilian nuclear energy represents yet another industry the United States and its enterprises pioneered, but which has experienced a significant (and potentially permanent) loss of U.S. capabilities.”

The case in point: there are 27 nuclear reactors currently under construction in China, with a whopping 150 proposed over the next 15 years. But throughout the last decade the United States, which once built dozens of reactors every 10 years, only built two. And while the average construction time for a nuclear reactor in China is seven years or less, in the United States these two new reactors each flew wildly over time and budget.

China intends to construct 6-8 new nuclear reactors per year, and at that pace it would surpass the US in nuclear energy generation by as soon as 2030. According to the ITIF, it took a mere 10 years for China to triple its nuclear capacity—something that took the United States nearly 40.

Construction on the Sanaocun Nuclear Plant, Zhejiang Province, China. Source: CGN

Where did this stupendous industrial capacity come from? In the 1990s, China modestly and gradually began the construction of reactor models sourced from other nations. The key catalyst in China’s nuclear energy boon was a 2008 agreement through which the US energy company Westinghouse licensed its AP1000 Generation III reactor technology to China. In 2010, hackers working with the Chinese military penetrated Westinghouse’s computer systems and stole what was left: confidential technical and design specifications for the reactor. These stolen materials became the basis for China’s copycat Generation III CAP14000 reactor, which forms the bulk of its new units.

Unfortunately, naive US scientists, who freely transferred an immense amount of valuable nuclear knowledge to a well-known predatory nation under the argument it would help mitigate climate change, are partly to blame for China’s rise.

But through these corrupt beginnings China has undoubtedly built a formidable commercial nuclear capacity. Its share of scientific publications is rapidly increasing, as the West’s proportion has steadily decreased. It was the first nation to begin construction of a Generation IV reactor, the gas-cooled Shidaowan-1 in the northern Shandong Province, the first to build an experimental molten salt and thorium reactor, and intends to be the first to construct a prototype of all six Generation IV technologies.

Number of top 10 percent most-cited publications in nuclear science and engineering, 2008-2022. Data from OECD, cited from ITIF.

Indeed, analysts believe China is 10-15 years ahead of the United States in capacity to deploy fourth generation reactors at scale. At the same time, it is gaining fast experience in the development of small modular reactors (SMRs). These SMRs, through their standardized design and mass production, can dramatically reduce costs in nuclear energy production. Meanwhile, the US only this year certified its first SMR design.

The six types of Generation IV reactors:

- Gas Cooled Fast Reactors (GFR)

- Lead Cooled Fast Reactors (LFR)

- Sodium Cooled Fast Reactor (SFR)

- Molten Salt Reactor (MSR)

- Supercritical-Water Cooled Reactor (SCWR)

- Very High-Temperature Reactor (VHTR)

The world’s first Generation IV nuclear plant (MSR), Shidaowan-1, China.

Source: Tsinghua University

Though the United States has been instrumental in developing these nuclear technologies, it has done next to nothing to make them a reality. And the chaos of Vogtle units 3 and 4, the only two reactors built domestically this decade, which went seven years over schedule and more than double over budget, has done little to whet its appetite for more.

Having good designs on paper is only one piece of staying competitive in a global market. The United States must demonstrate that it can construct them on the ground. As the ITIF bluntly states, “China is years ahead of the United States in even deploying our country’s own technologies.”

Policies Producing China’s Edge

As industry analyst Kenneth Luongo has commented, “They [China] don’t have any secret sauce other than state financing, state supported supply chain, and a state commitment to build the technology.”

Where China excels, and where the greatest lesson for the United States lies, is in its organizational and incentivization efficiency. China has worked to lower several immense barriers to the infamously expensive and difficult reactor construction process through streamlined permitting, low-interest financing, tariffs, and other subsidies that together quicken the process so that, taken together, Chinese plants cost only a third of those in the US according to the World Nuclear Association.

These policies include:

- Low-rate loans from state-backed banks that cover 70% of the cost of a Chinese reactor. Rates can be as low as 1.4%, far below what can be achieved by nuclear power companies in other nations.

- Generous subsidies that lower the cost of nuclear energy in China to $70 per MW-hour, far less than the $105 MW-hour cost in the United States.

- Generous value-added tax (VAT) rebates that reduce the operating costs of Chinese nuclear reactors up to 5-6% annually, an effective subsidy worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Furthermore, China’s considerable experience in recent global Belt and Road mega-projects has also contributed to supply chain and construction efficiencies generally unavailable to other nations. And as China continues to rapidly deploy ever-more modern nuclear power plants, it will over time produce significant economies of scale and learning-by-doing effects. This suggests that Chinese enterprises will gain an innovative advantage in the sector going forward.

In fact, China intends to market its nuclear reactor construction capabilities abroad as a part of its Belt and Road initiative, and its experience directly threatens US market share in this regard.

Leading exporters of nuclear reactors, country share of global market (2022). Data sourced from OECD, https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/nuclear-reactors, cited from ITIF.

What should the United States do?

According to the ITIF, the United States must develop a coherent national strategy and “whole-of-government” approach to reduce barriers to reactor development and regain its supremacy in the industry. If such a strategy were pursued, it would have the added benefit of an immense contribution to emission reductions the United States.

Comprehensive financial incentives like tax credits and relieve funds are desperately needed. The Department of Energy’s (DOE) Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program, which contributes billions to retrofitting aging reactors with more advanced technologies, is an important step in this process.

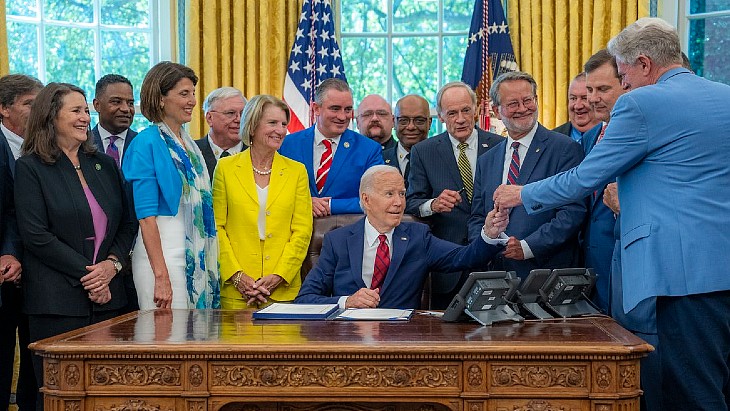

The newly signed ADVANCE Act is also a tremendous step forward. This law updates a regulatory system attuned to older Gen II reactors which did not possess many of the new technologies used in modern reactors, a system which required a myriad of time-consuming regulatory exemptions. The Act directs the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to reduce certain licensing application fees and authorizes increased staffing for NRC reviews to expedite permitting. It also helps fund competitive grants from the Department of Energy (DOE) to incentivize reactor designs and cover costs.

President Biden signs the ADVANCE Act, unleashing nuclear energy potential in the United States. Source: @POTUS on X.

The ADVANCE Act likewise directs the NRC to develop an 18-month permitting process for SMRs, widely regarded as the future of nuclear technology and in which China possesses a head start. The conversion of retired coal powerplants into small nuclear plants is also explored in the law.

Instituting programs which will reduce the cost per kilowatt generated closer to that of China, merely a third of costs in the United States, must also be accomplished. Thankfully provisions in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, which dedicated $6 billion and $40 billion respectively in investments and loans, represent a modest start. (China’s investment, by contrast, is $440 billion.)

Undoubtedly, one of the most important means of reducing China’s edge is through a strict embargo of nuclear knowledge transfer with the communist state. The naive exchanges of the past must never be repeated. Wisely, the ADVANCE Act bans the United States from purchasing certain fuel products from China, a key step that will reduce dependencies seen in other industries like green technology.

Lastly, a campaign to bring more students and professionals into the nuclear industry, to ensure there is enough manpower to stage America’s nuclear comeback, is critical. For in such a specialized industry, momentum is everything. The generational loss of a specialized workforce from the 1990s was one of the largest contributors to cost overruns in the Vogtle plant.

To all of this, the DOE optimistically states, “The ADVANCE Act, along with the historic investments and tax incentives provided by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, have truly reenergized our domestic nuclear power sector and repositioned us as a global leader on the technology we first developed.”

Let us hope that Congress continues to incentivize this great and promising sector. Though American leadership has been lost in so many industries as of late, we need not make nuclear energy production one of them.

By Evan Patrohay

Leave a comment