There is a golden rule that every ecology student learns on their first day of class: that everything is connected. Every species, even every individual, relies upon and is itself depended upon for the entire ecosystem to function. In a similar way, human beings associate into their own societal ecosystems–into a “political ecology” whereby the law of interconnectivity applies in equal fashion. But pernicious philosophies that advocate for ever more radical individualism, which have infected our society since the Enlightenment, threaten to upend the beautifully tangled web we are.

“Everything is connected” is the instinctual rhythm and heartbeat of an ecologist. It colors everything that we do. It is why a single extinction can have ripple effects throughout an ecosystem. It is why one nation’s emissions will eventually affect all. It is why the invasive ornamental plants we raise in our gardens often one day overtake the native vegetation beyond our properties. It is, ultimately, why ecologists seemingly incessantly attack and critique nearly everything that happens in modern society. Because, truly, everything we do in our society will have some environmental impact somewhere.

In nature, the principle of interconnectivity can be examined at the species and community levels in a variety of ways that can roughly be boiled down into two buckets: food web relationships and symbiotic relationships. Some overlap exists between the two.

A food web describes the relationship between species that depend on one another for their consumptive needs. Though sometimes simplified into a linear “chain” or “trophic” structure, whereby a herbivore is eaten by a predator, that predator is eaten by a bigger predator, and an apex predator lies at the top, such consumptive relationships are never so simple in reality. For instance, many species possess a preferred prey, but will consume others if needed. Environmental factors can also shift consumption chains in different directions at different times. For instance, in aquatic systems, increased sediment loads can shift available food from algae-heavy to bacteria-heavy sources as sunlight decreases.

Example of a simple food web. Source: Earth Reminder

Furthermore, what lower-order organisms eat, and how much they eat, affects the organisms that eat them in what are known as trophic cascades. In other words, available resources are always in flux depending on the rate they are consumed. Because consumptive patterns exist in nature as “chains” of species, populations in one link of the chain depend on the populations of all the other links above and below them. This places every population in a constant, cyclical relation with all others.

A famous example of this comes from studies on the relationships between Canadian lynx and snowshoe hare populations in the Arctic north. When lynx are abundant, they consume more of the hare population and it becomes suppressed, meaning the vegetation the hares eat becomes more abundant. When the lynx run out of enough hares to support their population, the hares are released from consumptive pressure and rebound in number, meaning the vegetation they eat then becomes suppressed.

The result of this interplay of species and resources is a complex web of both direct and indirect dependencies. The same is observed in society.

Because only a negligible minority of human beings actually eat each other, the consumptive relationships of species in nature are analogous to our material consumptive relationships in society, both as individuals and as corporate institutions like companies and governments. In society, as in nature, all compete for limited resources. And likewise to nature, every entity in society depends on the others in some way for the materials it needs to survive–whether that be to live as an individual or function as a business. In the past this operated predominantly at the community level; village residents depended on the particular crops each would grow, the particular skills its tailors and blacksmiths would use, and so on. The material interconnectedness of society has become even more apparent as our economies have grown, our reliance on consumerism and mass-manufacturing supply chains becomes stronger, and our self-sufficiency decreases (think of Milton Friedman’s famous “I, Pencil” speech).

In nature, populations cycle through time and fluctuate around a theoretical limit ecologists call carrying capacity, which represents how many animals can be supported by the ecosystem’s available resources at a given time. In society, the fluctuation around a carrying capacity is analogous to how supply and demand fluctuate around their own average–the famous “intersection of the curves.” And though we try our hardest to create stability, our markets often move in cycles too.

The classic supply-demand curve.

Like consumptive chains in nature, our supply chain is best represented by just that, a chain. This means that the consumption at any one link in our own consumptive chain depends on all others that come before and after it. Recall during the early days of Covid when manufacturing chains were mobilized to produce breathing ventilators or vaccines. At first there was scarcity in supply, but soon a glut in the materials was produced and the demand was lowered. This is like the example of the lynx and hares, which are constantly fluctuating between scarcity and abundance.

In one way, this reveals how markets are perhaps the most natural form of organization for human beings. In another way, it reveals just how unstable a market can become when one or more of its inputs change (as we all witnessed during Covid’s supply chain impacts), as in an ecosystem if a species is driven out or goes extinct. Like ecosystems, markets can be at once highly resilient and highly vulnerable.

Notice that in human supply chains, which are made by us, patterns of consumption are induced by demand, or the will of the individual. But in nature, which was made by God, patterns of consumption are an emergent trait not dependent on the will of the animals. Thereby, our societies are far more reliant on the personal relationships of individuals.

The interdependence of a market is one example of how reliant we are on others and is highly analogous to a food web in ecology. At some level, however, market-based relationships can be more mechanistic and impersonal in practice depending on the industry and how far separated a link in the chain may be geographically from others. But there is another far more moral and intimate way in which humans depend on one another, and that is in our participation in community and institutional life, represented in the ecological world by symbiosis.

Symbiosis is a broad term that describes any type of interaction between organisms. There is both obligate symbiosis, where the organism depends on another for survival, and facultative, where the organism could still survive on its own.

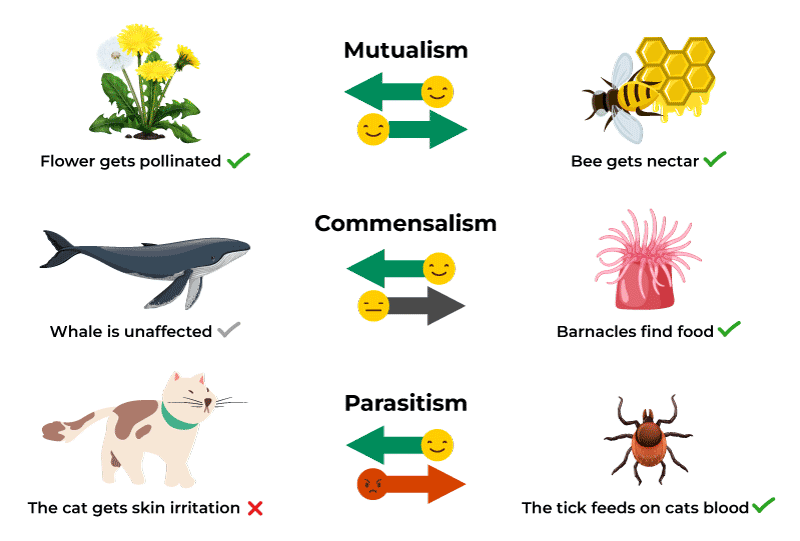

There are many types of symbiotic interactions. In every interaction, one of the parties either benefits, is harmed, or is unaffected. Competition is perhaps the most easily identifiable symbiotic interaction, and is considered harm-harm, since neither organism receives the full amount of resources it would have without that competition. In commensalism, one is helped while the other is unaffected, such as when a spider spins its web between the leaves of a plant. In mutualism, both benefit, such as the algae which form roommates with coral polyps, the former sharing food with the latter and the latter providing a home for the former. There are several other lesser discussed examples of symbiosis.

(Very interestingly, “competition” is always regarded as a harm-harm relationship in ecology, while in society most classical liberals and libertarians believe it to always be a win-win. This dichotomy merits a further discussion at a later date. Why might competition be more beneficial in a human society but not in nature? I suspect the reason lies behind the remarkable ability for humans to grow and adapt in response to scarce resources, while the nature of animals remains more fixed.)

Common examples of symbiotic relationships in society. Source: Geeks for Geeks

In society, there are many angles from which symbiosis can be examined, both material and moral. All angles further display just how reliant we are on one another. Society itself, of course, is a sort of symbiotic relationship between a government and its people. It is an overarching relationship of law and order, where the latter agrees to obey the law and the former to enforce the law, and it is intended to create an environment through which other mutually beneficial relationships can form. If you believe the Enlightenment social contract theorists (which I don’t), society was formed from some explicit agreement between people and state in the past for the sole purpose of enabling the people to practice their individual freedom. If you believe the conservative empiricists (which I do), the broader relations of society form implicitly from the bedrock of the smaller mutually obligatory relations of families and communities.

However, “community life” has become another one of today’s unfortunate and increasingly meaningless buzzwords because of its propagation by many who approach communities like a scientist observing a specimen, and by government bureaucrats and politicians who wish to “grow communities” merely by pumping their own ideologies into them and reforming them into their own artificial image. This is exactly what I have witnessed during my time in government.

I believe symbiosis in society is represented best through the function of institutions. Yuval Levin defines institutions in his book, A Time to Build, as “the durable forms of our common life…the frameworks and structures of what we do together.” They are a “way to give shape, place and purpose to the things we do together.” By this understanding, institutions, be they families, schools, churches, governmental bodies, or otherwise, are one of predominant ways symbiotic relationships may be developed in society. To return to the food web analogy, they are what give form and shape to the lines we draw within our societal web.

Much as a tree provides the form and structure for which multiple species may find their habitat and rest in a forest, institutions are the places where individuals form their niche and “habitat” in society. As Levin writes, they form our place in society because they are what we “pour ourselves into.” Further, as Yoram Hazony explains in Conservatism: A Rediscovery, the institutional bonds of society stem from our mutual obligations to one another, in the ways that we share and receive honor, and in the ways we help those who depend on us and on whom one day we may depend.

However, there are many who deny the obvious realities of societal relations, instead subscribing to the belief, characterized by the philosophy of liberalism, that “consent is the basis for political and moral obligation.” In other words, that all relations in society do not stem from obligations but instead from individual choice.

The overwhelming pull of the individual in American (and Western) society has instilled the false impression upon us that, to return to an ecological metaphor, our connections are facultatively instead of obligatorily symbiotic. Treating individual freedom like a religion, we falsely mislead ourselves to believe that we could get along just fine as an atomized individual–and worse, that our responsibilities towards others actually impede and harm us. Treating our lives this way is analogous to another scientific metaphor: that of the thermodynamic law of entropy, which states the universe inherently tends toward dissolution.

Examples of major social institutions. Source: EssayCorp

Hazony sees things differently. He writes, “There can be no human society in which individuals are loyal only to themselves.” In science, some form of outside energy is required to organize dissolute molecules into higher forms of order. In society, mutual loyalty and obligatory relations provide this energy, and are the reversal of social entropy. Hazony writes, “Feelings of mutual loyalty pull individuals together, forming them into families, clans, tribes, and nations, just as the force of gravity pulls molecules together, forming them into planets, star systems, galaxies, and systems of galaxies.”

When all citizens are invested and active in their institutional niches, society functions fluidly and healthily, just as in an ecosystem. Note that there remains a diverse plethora of these institutional niches in society, again just as in a true ecosystem. Therefore, in a beautiful way, acting within one’s given niche and performing one’s given function as part of a larger whole, preserves a substantial degree of individual freedom within their obligations. We all must ask ourselves how to act given our niche (or as Levin writes, ask: “how do I act given my role here?”), but we can never attempt to release ourselves from our political and moral bonds simply because we choose not to be obligated to them any longer. In nature, no animal can choose to reject its station.

While mutualism is therefore the reigning symbiotic relation of human society, especially in an institutional context, commensalism is likewise apparent in all places. The latter relation describes the ancillary benefits we receive from the fruits of the work of others around us. Even if I do not hold a position on my local school board, my children still benefit from the wise counsel of those sitting on it. Though I am not yet a father, I have benefited from my father’s teaching and guidance, and indirectly benefited from how his father instructed him.

Societies, like ecosystems, are dynamic in both time and space; the degradation or absence of any niche within them has ripple effects that begin to unravel the whole both spatially and temporally. The decisions of our ancestors, and the institutions they left behind, are thus the supreme example of commensalism in society. Who can number the benefits we have reaped from our Founders and others who through our 250 years have strived to ensure we live ever closer to the ideals they gave us? In the same way, we, the living, have a responsibility to keep our institutional niches functioning to benefit those who will come after us.

Critically, conservation requires strong social institutions to organize support and care.

Source: Greenargen.com

Instead, as more of our people tend towards a selfish, hyper-individualistic, liberal mindset, we leave the realm of mutualism and commensalism and enter that of parasitism, the last major symbiotic relation we have left undiscussed. In parasitism, one party benefits while the other is harmed. The more people who desire to “mooch” from the labors of others in our nation without giving back in any way, the more the social fabric wears down.

“Parasite load” is a concept that describes the ratio of parasites to other organisms in an ecosystem, and it can reach thresholds so burdensome that it leads to the extirpation of species and the extinction of niches. In our nation we ought to discourage “parasites” in all forms within reason, whether that be in welfare, border-crossings, artificial intelligence, or growing anti-work cultural sentiments.

I hope that this exercise has enabled the reader to see just how many parallels there are between society and nature–and how connected we all are as a consequence. We are individuals, yes. But, as Aristotle famously said, we are social animals too. Our relations are therefore obligate and not facultative towards one another; our whole depends on all its parts. Any ideology that advocates for radical individualism, like the liberal paradigm, thus threatens to untangle the interconnected and mutually beneficial web we are.

By Evan Patrohay

Leave a comment